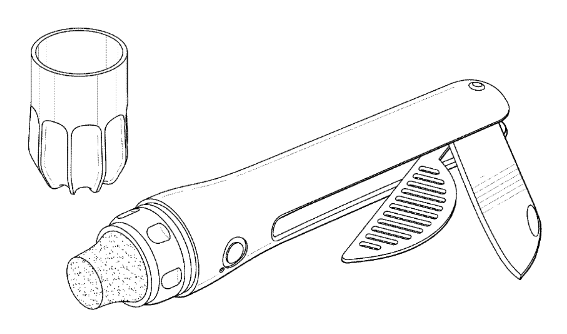

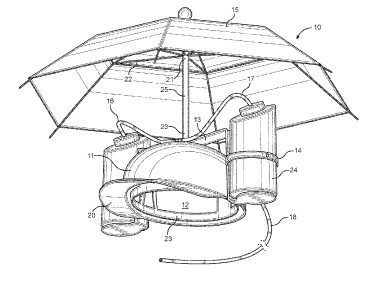

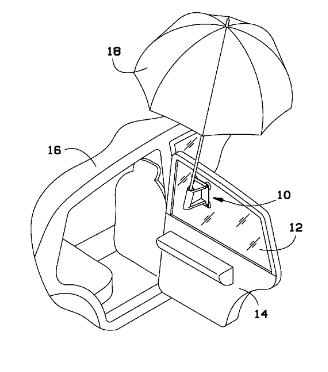

In Zircon v. ITC, [2022-1649] (May 8, 2024), the Federal Circuit Court affirmed the ITC determination of no violation of section 337. The case involved U.S. Patent Nos. 6,989,662, 8,604,771, and 9,475,185, on electronic stud finders.

To establish a section 337violation, Zircon was required to show that “an industry in the United States, relating to the articles protected by the patent . . . exists or is in the process of being established.” 19 U.S.C. § 1337(a)(2). This is referred to as the “domestic industry” requirement. The ALJ found that the economic prong of the domestic industry requirement was not satisfied with respect to any of the asserted patents. The Commission upheld the ALJ’s determination that there was no violation of section 337, for two independent reasons. First, with respect to the domestic industry requirement, the Commission affirmed the ALJ’s determination that Zircon had not satisfied the economic prong of that requirement. Second, the Commission found each of the claims of the ’662, ’771, and ’185 patents that were before the Commission were either invalid or not infringed.

To meet the domestic injury requirement, a complainant can show that, “with respect to the articles protected by the patent,” there is “(A) significant investment in plant and equipment; (B) significant employment of labor or cap-ital; or (C) substantial investment in its exploitation, including engineering, research and development, or licensing.” 19 U.S.C. § 1337(a)(3)(A)–(C). That provision is referred to as the “economic prong” of the domestic industry requirement.

Zircon has relied on evidence of its cumulative expenditures on all 53 of its domestic industry products to argue that its investments in plant and equipment, labor or capital, and/or research and development have been significant or substantial. Zircon had acknowledged, however, that not all 53 products prac-tice all three of the asserted patents. Rather, Zircon’s evidence showed that of the 53 products, 14 practice all three of the asserted patents; 21 practice both the ’771 and ’185 patent; 16 practice only the ’662 patent; and two practice only the ’771 patent. Zircon did not allocate its expenditures on its 53 stud finder products separately with respect to each of its products or each of the asserted patents. The Commission found that Zircon’s failure to do such an allocation precluded the Commission from evaluating the significance of Zircon’s investments with respect to each asserted patent.

On appeal, Zircon argued that the Commission erred by requiring a patent-by-patent breakdown of its investments and that, in doing so, the Commission departed from its “flexible, market-oriented approach to domestic industry” in Certain Wireless Devices with 3G and/or 4G Capabilities & Com-ponents Thereof, Inv. No. 337-TA-868, USITC Pub. 4475, Initial Determination at 413 (July 29, 2013).

The Federal Circuit found the ITC actions were consistent with Federal Circuit precedent, noting that it has held that where a party seeks to rely upon research and development activities, it must show that those activities the complainant must show that those activities “pertain to products that are covered by the patent that is being asserted.” The Federal Circuit explained that “[i]n cases in which all the domestic industry products practice all the asserted patents, it follows from the language of section 337 and our case law that the complainant could satisfy the economic prong as to all asserted patents based on the entire product group. But in cases in which the complainant’s products or groups of products each practice different patents, the complainant would need to establish separate domestic industries for each of those different groups of products.”

Zircon further argued that in a case such as this one, the Commission’s analysis should proceed on the basis that there is a single industry which exploits the patents. But the Federal Circuit distinguished ZIrcon’s precedent because Zircon sought to aggregate were not all protected by the same patent or patents. The Federal Circuit noted that Zircon might have been able to show the substantial or significant investment requirement was met by its investment in the 14 products that practice all three asserted patents, but Zircon provided no way for the Commission to assess the significance of Zircon’s investment in that product group because Zircon presented its investments in the aggregate for all 53 products, which practiced multiple different combinations of patents.

Because it upheld the Commission’s ruling on the domestic industry issue, the Federal Circuit said it was unnecessary for it to reach Zircon’s challenges to the Commission’s infringement and invalidity rulings.